A startup’s guide to disruption

Disrupting healthcare. Disrupting real estate. Disrupting the financial landscape. Disrupting billion-dollar industries.

“Disruption” is a cliché in the world of technology and startups nowadays, and it has taken on a rather vague meaning in recent years. Most startups claim they’re disrupting something even if they just mean they’re applying some new buzzwords to an old problem. But if you are someone who is starting up, it’s extremely useful to trace back the origins of what “disruptive innovation” actually is and understand the real patterns that underly this phenomenon so that you can use them to your advantage.

“Disruption” as it relates to technology can be traced back to 1995, where it first appeared in a journal article authored by Clayton Christensen and which became the genesis for “The Innovator’s Dilemma” – a book derived from research he did at the Harvard Business School. Christensen is somewhat of an oracle in business management circles and his book was one of the first to posit the theory that companies don’t succumb to disruptive competitors due to mismanagement, but because they are managed too well.

Through a series of well-researched industry case studies, Christensen highlights countless examples of companies that have succumbed to disruptive innovations, including IBM, Harley Davidson, Xerox, Reuters, and Kodak – companies that have created some of the most iconic products in history. These case studies show that past success is no guarantee from innovative failure and success is in fact one of the reasons why companies fail to capitalise on disruptive innovations in the first place (even when they are the ones that discover the technology that ends up fueling the disruption).

One of the key points in the book is that there are two types of innovation that a company can undertake. One type of innovation represents a growth opportunity for a successful company, the other is an existential threat to the company itself. Most companies in a market are constantly investing in the former – updating their technology to make their offerings cheaper and better. Those incremental improvements are called “sustaining innovations” and are ones that incumbents in a market generally keep pace with. Even if they are late to the party, most well-performing companies can play catchup with their competitors and reap the benefits of sustaining innovation.

“Disruptive innovations” – the sort that cause unassailable companies to be toppled by scrappy startups – start small, away from the view of market leaders, and scale up to be giant-killing tidal waves. The key is that these innovations look thoroughly unattractive from the outset: they perform worse, they cost more, and they command pitiful profit margins and market sizes. That is what makes them so unattractive to incumbents. But over time technology always gets better, costs can be amortised, and markets can grow.

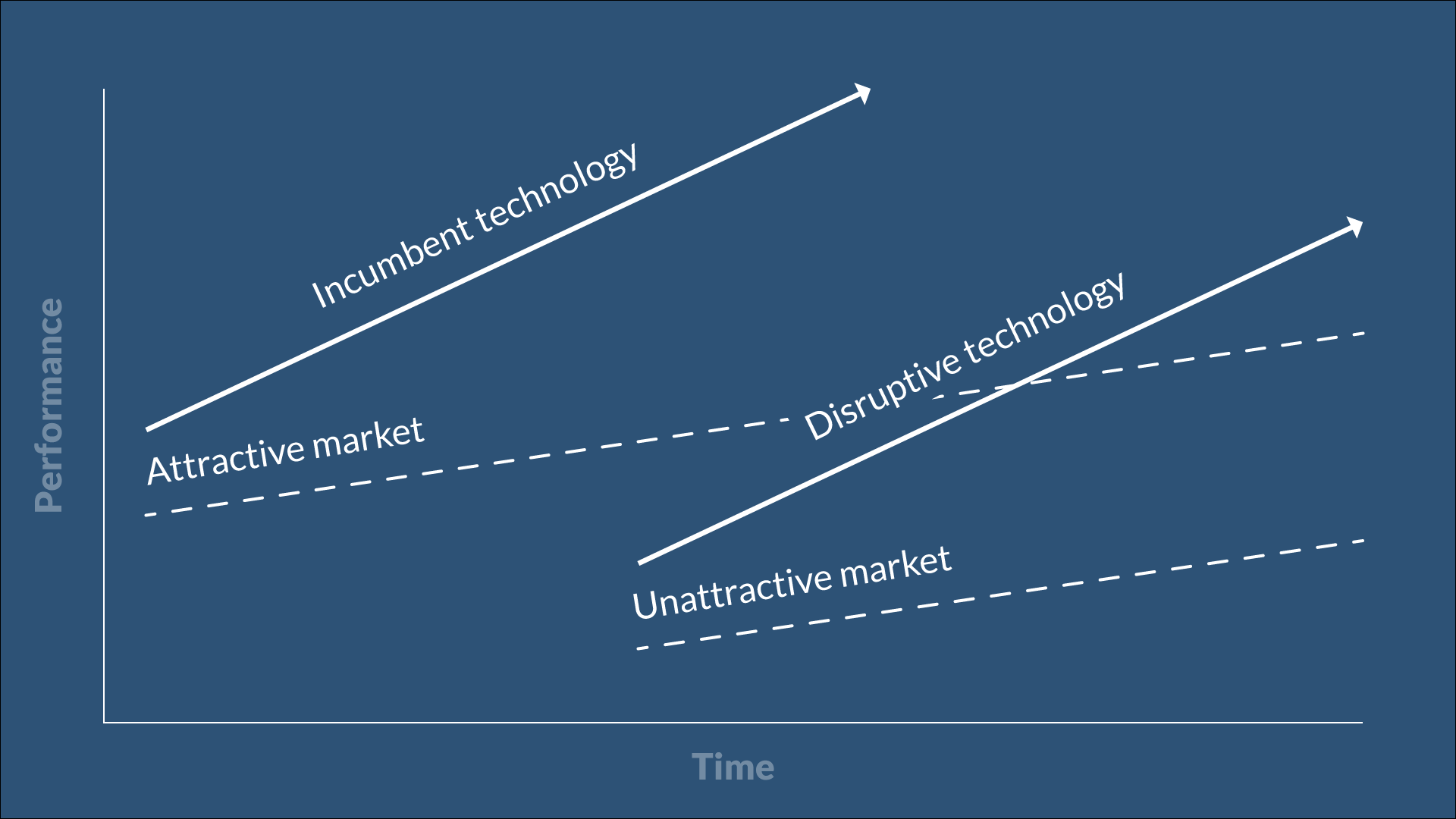

This recurring pattern can be visualised with a trajectory graph:

What does this all mean? Often a disruptive innovation will be worse on a number of axes that an incumbent highly values but better on one that they ignore. A good example of this is in the hard drive industry – most of the time customers value the amount of data storage as their primary measure of performance, so manufacturers will organise their improvements based around increasing storage size. But every now and then a market will begin to appear that values some other measure of performance, such as smaller physical dimensions of the drive. This measure of performance will trump the normal measure and mean that customers are willing to accept “worse” performance in order to satisfy their other needs. If a product comes along that satisfies their needs for size then they will latch onto it.

There is a double mismatch here for incumbents in both market and technology. The market size isn’t big enough for them to be interested in, and the technology isn’t performant enough for them to use, so they invest their money elsewhere (often in sustaining innovations).

Because of these factors it is extremely hard for a company to move downmarket; it is a lot easier for a company to move upmarket. Once an organisation has built a value network based around a particular technology, with particular customers, and particular levels of profit margin, it is extremely hard for them to embrace a worse-performing technology that doesn’t suit their existing customers and has much lower levels of profit margin. But for a company that starts off by organising its structure around the disruptive technology and optimising its cost structures for lower levels of margin, moving upmarket looks extremely attractive. And as soon as their technology becomes good enough to meet the performance demands of the higher market they can start stealing market share from the incumbents. They operate leaner, so they offer better value and make the switching decision easy. The disruption has now been realised.

While Christensen’s books generally focus on learnings for incumbent companies looking to kickstart their innovation, it is easy to draw lessons out of his analysis for startups that are just beginning their journey and aiming to find traction amidst a sea of competitors. I’ve seen many people flounder with their new products, trying to think of ways to get millions of happy people to switch from a well-developed incumbent by just offering a 5% improvement on the way they’re doing things already. The key is to find a market who’s really different, who values your technology for its uniqueness. Build a product which celebrates its differences and use that success to springboard your company to bigger opportunities.

Cameron Adams is a co-founder and Chief Product Officer at Canva, where he leads the design & product teams and focuses on future product directions & innovative experiences. Read a bit more about him ›

Cameron Adams is a co-founder and Chief Product Officer at Canva, where he leads the design & product teams and focuses on future product directions & innovative experiences. Read a bit more about him ›